- UID

- 20

- Online time

- Hours

- Posts

- Reg time

- 24-8-2017

- Last login

- 1-1-1970

|

Editado por Pedro_P en 15-2-2018 06:07 PM

When sociologist Richard Sennett was fleeced by an iPhone dealer in Delhi, the pair struck up a friendship that opened a window into the informality of modern cities.

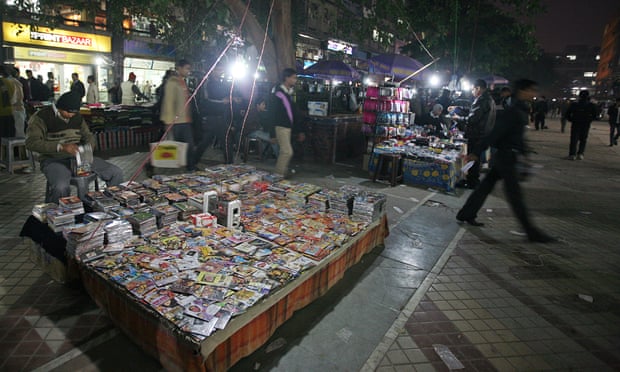

A trader outside a commercial complex in Nehru Place, New Delhi. Photograph: Bloomberg/Getty Images

In the south-east of Delhi, a vast T-shaped market has arisen on top of an underground parking garage.

Nehru Place came into being because in the 1970s Delhi did not have enough commercial real estate to house its burgeoning small businesses. Original plans show the plaza above the parking garage as empty, and lined with low, four-storey buildings meant for offices rather than shops. Today, there remain traces of that intention. The boxy buildings lining the sides of Nehru Place form a downmarket version of Silicon Valley. Here, tech startups occupy cramped rooms next to computer repair shops and cut-rate travel agents.

The open-air plateau, however, has filled up with retail stalls. Here, people sell smartphones, laptops and pre-owned motherboards, saris and Bollywood CDs, sometimes all out of the same boxes. Crowds surge with energy. In the multiplex, the same Bollywood film has been cut and edited differently for the three languages in which it is currently showing. Nearby is a huge temple, and also more upscale office buildings.

People mingle casually on this plateau. Unlike Silicon Valley, where everybody makes a point of dressing down, the budding entrepreneurs of Nehru Place flaunt designer jeans and expensive loafers. Yet they do not hold aloof from the heaving market; a very good food stand, for instance, is located outside the offices of a firm that has pulled off an IPO. Rather than lunch in an upmarket place, the sharp young men still hang out around this stand, eating off paper plates, gossiping with the stand’s half-blind, motherly proprietor.

At night, India’s ghosts appear: pavement dwellers who colonise the staircases or spread out under the few trees that offer some shelter against the weather. One night I watched the police try to sweep out these night dwellers. As the forces of order moved forward, the dispossessed regrouped behind them and bedded down again – as the police knew perfectly well they would.

Nehru Place, a down-market version of Silicon Valley. Photograph: Richard Sennett

This mixed scene does not quite evoke Jane Jacobs’ West Village. Though loose and micro-scale in the character of its daily life, Nehru Place came into being thanks to large-scale, careful planning. Big money has been spent to provide Nehru Place with its own metro station and an equally efficient bus terminal. Slightly elevated and angled, keeping out rain and draining filth, the garage roof – though unlikely to win any architecture prizes – is a masterstroke in terms of urbanism. On top of it, what the French call acité(a neighbourhood with character) has become grafted on to a plannedville.

It’s misleading to imagine that the poor only appropriate unbuilt land. Many places they colonise were previously constructed for a purpose, lost their value for one reason or another, were abandoned and then appropriated. Nehru Place is the same: unforeseen rooftop activities over a structure whose original purpose was parking cars.Mr Sudir's situation is familiar, if uncomfortable morally – ethical family values coupled to shady behaviour

It is also typical of the informality that marks other fast-growing (or in UN-speak, “emerging”) cities. Economically, the entrepreneurs of Nehru Place have escaped India’s legal marketplace, which had suffocated under a leaden bureaucracy. Legally, they sell what are politely described as “grey goods” – at worst stolen or, less bad but still illegal, diverted from factories or storage facilities, untaxed.

Politically, as with the pavement-dwellers and the police, Nehru Place is informal in the sense of not being rigidly controlled. Socially, it is informal because of its transience. Shops and shoppers, offices and workers come and go; the stall you remember from last month is no longer there. The half-blind, motherly kebab-seller seems, at least in my experience, the only permanent fixture. Informal time is open-ended.

Versions of Nehru Place can be found in a Middle Eastern souk or a parking lot in Lagos; they used to appear in the squares of almost any small Italian town. In all of them, sellers and buyers haggle in a kind of economic theatre. The merchant declares, “This is my rock-bottom price!” to which the buyer responds with something like: “I really don’t want this item in red; don’t you have one in white?” The seller, discarding the “rock-bottom” declaration, answers, “No, but you can have it in red wholesale.”

The Parisian department store put an end to this. In its windows, commodities were still dramatised, but prices were fixed. The “grey market”, on the other hand, fosters a certain kind of face-to-face urban intensity.

The business people of Nehru Place have escaped India’s legal marketplace. Photograph: Mail Today/India Today Group/Getty Images

I learned this to my cost in Nehru Place. I first came here in 2007, to hang out rather than to work. (The LSE was holding a conference in Mumbai that year, and I wanted to see more of Indiathan the inside of a conference hall.) But my phone – an early iPhone – had gone on the blink, and someone gave me a tip: a repair genius near the south-west corner of Nehru Place. I found the spot, but not the man; he had “been moved on”, said a young woman nearby, which my local colleague interpreted as, “he has refused to pay the right bribes”.

If I couldn’t repair my phone, I had to find a replacement, which was not an extravagant expense here. Many goods are cheap because, as one merchant declared of a box of new iPhones, all in red: “It happened to fall into our hands.” It was he who offered to do a deal “wholesale” – and we did it, on an overturned cardboard box that served as his shop counter.

He sold me a dud. I returned two days later and demanded my money back. The Indian friend with me released a volley of what sounded like quite threatening Hindi, and a new phone was handed over. The iPhone merchant then smiled, as though this was just part of the working day.

Rather than a slick youngster, he was a balding, paunchy man, reeking of some sort of perfume that perhaps also “happened to fall into our hands”. What touched me was a framed photo of two adolescent children he set on the upturned cardboard box.

‘I am Mr Sudhir’

It was insufferably hot, and I was pouring with sweat. Having placated me, the merchant offered tea, the hot liquid somehow assuaging the heat. We sat on either side of the box, stained with the rings of prior teacups – refreshment for assuaged customers was also normal business practice. I told him I was a researcher. He replied: “I am Mr Sudhir.”

Sudhir is a first name, and my host, evidently believing all Americans use them when meeting strangers, used his own, perhaps adding the “Mr” as a signal that I should treat him with respect. After selling another red iPhone to a wandering Dutch woman, his eyes carefully averted from me, Mr Sudhir returned to our conversation. We had already discussed grandchildren, and his own story now appeared.

Mr Sudhir had received a few years of schooling beyond the norm in a village 50 miles away, which perhaps prompted him as an adolescent to seek his fortune in Delhi, however he could. Contacts had put him into Nehru Place – but originally in the fetid stalls in the parking garage, home to the most marginal traders.

Electronic shops in Nehru Place. Photograph: Bloomberg/Getty Images

“In the garage it was hell,” Mr Sudhir said. “I had to be watchful every moment.”

In time, he rose above ground, occupying one regular spot and becoming known to a few key contacts outside.

As we talked, I heard other voices. In the 1980s I had made a study of 14th Street in New York City with the photographer Angelo Hornak. In those far off pre-gentrified days, that big street resembled Nehru Place in one key way: 14th Street sold towels, toilet paper, luggage and other everyday goods which “happened to fall into our hands”. The goods were available because freight operations at John F Kennedy International airport would “leak”, we were told. This grey market of 14th Street served as the public realm of working-class New York: almost all the underground lines in the city converged on it, and out on the sidewalks, in front of the stores, were overturned cardboard boxes like Mr Sudhir’s.

I became acquainted in particular with a group of African migrants who manned some of those cardboard boxes on 14th Street between 6th and 7th Avenues. They were men just hanging on, earning a few dollars each day, sleeping rough in basement corners or outside, but immensely proud. My passable French served as an entry card to stories of long, erratic journeys from West Africa, of politics or tribal conflicts that had aborted jobs, landed sons in prison, daughters in prostitution. The escape to America was filled with guilt over abandoning home, yet it had not improved their fortunes. Their life’s journey led relentlessly downwards, and they were depressed.

Dodgy dealings have led Mr Sudhir in the other direction. Abjection to him meant hawking stolen goods in the depths of Nehru Place. But he made a move up, both literally and socially, and the fact that he traded in goods of dubious origin did not detract from his aura of solid paterfamilias. The market offered him a chance to establish a solid stone on which his two sons could stand when they took over the business.

Street vendors selling an array of umbrellas, leather bags, watches and sunglasses on a New York street in 1979. Photograph: Frances M Ginter/Getty Images

It was the same, I learned, with his house. In the course of the 20th century, as the urban revolution gathered force, the mass of poor people streaming into cities occupied empty land to which they had no legal right. By one estimate, 40% of new urbanites in the year 2000 squatted in cinderblock or cardboard shacks. Private owners now want their property back; governments see these shack-camps, if made permanent, as a blight on cities.

Mr Sudhir, who has squatted for 14 years, doesn’t see it that way. Year by year he has improved his house, and he now wants to secure these improvements by making his tenancy legal. “My sons and I have recently added a new room to our home,” he told me proudly. They’d built it each night, cinderblock by cinderblock. The anthropologist Teresa Caldeira has noted that such long-term family projects become a disciplining principle for how money should be spent over the years. The collective efforts are a source of family pride and self-respect. Mr Sudhir has a family to support, and a dignity to maintain.

His situation is a familiar one sociologically, if uncomfortable morally – ethical family values coupled to shady behaviour. The harsh conditions of survival can put poor people in that position; taken to a more violent extreme, it is the story told in Mario Puzo’s The Godfather. I cannot say that my sympathy for Mr Sudhir as a paterfamilias made me accept being fleeced by him. Still, I wasn’t very angry. Need, rather than greed, drove him, and he wasn’t a self-righteous crook.

Our tea should have been an unalloyed moment – one old man sharing with another the fruits of a life of striving. But looking around us in Nehru Place, he concluded our chat with the comment, “I know I will be pushed out.” It was survivor rather than victim talk. “At our age,” he added, “it is not easy to start again.” But he then named a number of other places in Delhi where he might set up shop once more, illegally. What are the forces that seek to push out this admirable conman?

This is an edited extract from Building and Dwelling by Richard Sennett, published by Penguin.

Source |

|