- UID

- 20

- Online time

- Hours

- Posts

- Reg time

- 24-8-2017

- Last login

- 1-1-1970

|

|

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

Claimants are given a 12-digit number linked to their data, and if something goes wrong they can be refused food.

A villager goes through the process of eye scanning for UID database system at an enrolment centre at Merta district in Rajasthan Photograph: Mansi Thapliyal/Reuters

▼ Motka Manjhi had been back and forth to the ration shop four or five times, his wife said, but on each occasion he returned empty-handed. His thumbprint, needed to prove his identity, wasn’t registering on the new system.

He was told to do an online update. But to do so he would need to get to a private centre – a four-mile journey from his village in Dumka, in the state of Jharkhand, north-east India. This would mean missing at least a day’s potential work, which he desperately needed to buy food. And even if he made the trek, there was no guarantee that the system, which often suffers from network outages, would be working properly. What was to be done?

In the past, Manjhi and other low-income Indians only needed papers to pick up subsidised grains to feed themselves. But the welfare system in India has undergone dramatic change.

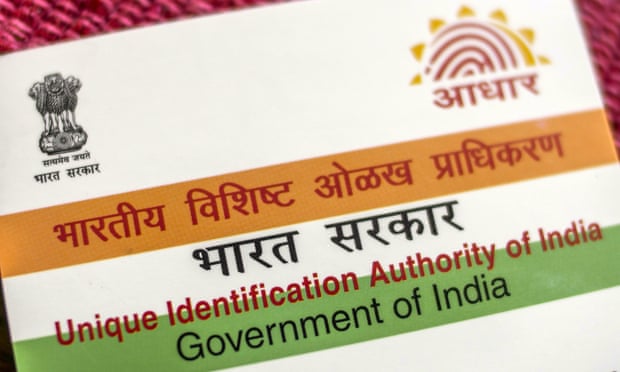

Each person claiming support is now required to have an Aadhaar, a unique 12-digit number that is linked to their biometric and demographic data. The scheme has grown so quickly since its introduction in 2009 that it now covers more than 1.2 billion people and is the world’s largest biometric identification system.

The Indian government argued that this system would revolutionise welfare: computerised checks would stop fraudsters from siphoning off other people’s benefits, allowing more money to reach the poor. But campaigners say its design is flawed and it is riddled with technological glitches. They argue it has become a Kafkaesque nightmare that has caused misery for the very people it claims to protect.

Despite the serious concerns raised by economists and poverty experts, the system kept on growing and is now involved in access to anything from a pension to medical reimbursements or disaster emergency relief. Activists say in some cases parents are wrongly being asked for an Aadhaar number in order to enrol their children in school.

If there’s a fault in the system, access to an array of support can abruptly halt. “Decisions about you are made by a centralised server, and you don’t even know what has gone wrong,” said Reetika Khera, an associate professor of economics at the Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad. “People don’t know why [welfare support] has stopped and they don’t know who to go to to fix the problem.”

An Aadhaar biometric identity card. Photograph: Bloomberg via Getty Images

Even if a person is lucky enough to find out what has caused the disruption, this doesn’t mean the problem will be solved (▪ ▪ ▪)

► Please, continue reading this article here: Source |

|